The Brazilian higher education system underwent its most important reform in 1968, which incorporated the principle of integration between teaching and research, based on the model of research universities in the United States, with their graduate schools, departments and institutes, credit systems, PhD professors and full-time students. One of the important results of this reform was that, as scientific research expanded in the country, it did mosty within higer education institutions. However, while trying to emulate the North American system, the reformers ignored that the research universities were just one part of a much larger system of mass higher education, with thousands of institutions with other characteristics. In the ensuing years, the Brazilian higher education sector also expanded, overflowing the limits of the research universities idealized in the 1960s. Since then, Brazilian legislation has sought to accomodate the new reality of a complex system of public and private institutions of teaching and research, on-site and at a distance, without, however, having had a comprehensive reform that could account for the diversity that was occurring.

The Project “Research and Innovation Research”, conducted by the Department of Science and Technology Policy at the Institute of Geosciences at Unicamp, with support from FAPESP, aims to understand the different contexts and modes of support for scientific and technological research in the country. Part of this work consists of understanding in greater depth how higher education in the country has been changing, and the places of undergraduate teaching, graduation courses and research in this system. Between 2010 and 2020, access to higher education in Brazil increased by about 30%, from 6.6 to 9 million students, including those enrolled in undergraduate and strict sense postgraduate courses. It was not a homogeneous growth: Brazilian higher education, as in the rest of the world, is strongly differentiated, with public and private universities, major distance learning institutions, selective and easier access institutions. To better understand this difference, in a previous work, we proposed a classification of undergraduate and postgraduate education institutions into nine types, mainly considering the size of the institutions, in terms of the number of enrolled students; its legal or institutional nature; and the relative weight of their dedication to undergraduate courses in their different modes (bachelor’s and teaching degrees, technological courses) and stricto sensu postgraduate courses (master degrees and doctorates).[1]

For an overall view, it was necessary, at first, to unify the databases of the Higher Education Census of the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP), with information referring to undergraduate courses, and CAPES, with information referring to postgraduate courses, taking the year 2018 as a reference. Subsequently, we had access to the CAPES database for the period from 2004 to 2020 and the INEP database for the period from 2010 to 2020, organized by Fapesp. As INEP and CAPES do not use the same codes and criteria to identify entities and organize information (keeping it together or separately, with no uniform criteria, institutions and their different parts or locations) and as Capes microdata had not been submitted to a proper systematization and cleaning, like INEP’s, meticulous work was required to organize the data, including the creation of a common dictionary of entities and a series of decisions about aggregation and elimination of inconsistent information. To these two sets of data, we added information on scientific publications from the Web of Science and other data from INEP referring to student flow and of socioeconomic characteristics of undergraduate students.

The integration of these different databases allows different analyses on the characteristics and recent evolution of Brazilian higher education, which will be presented in subsequent working papers.

Typology

There are two ways to develop a typology: by statistical methods, which allow grouping entities according to their similarities or differences, and using more or less arbitrary criteria, however supported by the observation of the most relevant data. In a recent piece of writing, Maria-Ligia Barbosa and collaborators carried out a hierarchical cluster analysis of the principal components of a large database of Brazilian higher education institutions, based on information from the 2019 INEP Higher Education Census, which led to the identification of four groups: 1) private, small and inclusive colleges (35% enrollment); 2) small colleges with an emphasis on vocational training and STEM (1.3% enrollment); 3) large private universities (40% enrollment); and 4) large academically oriented public universities (27% enrollment).[2]

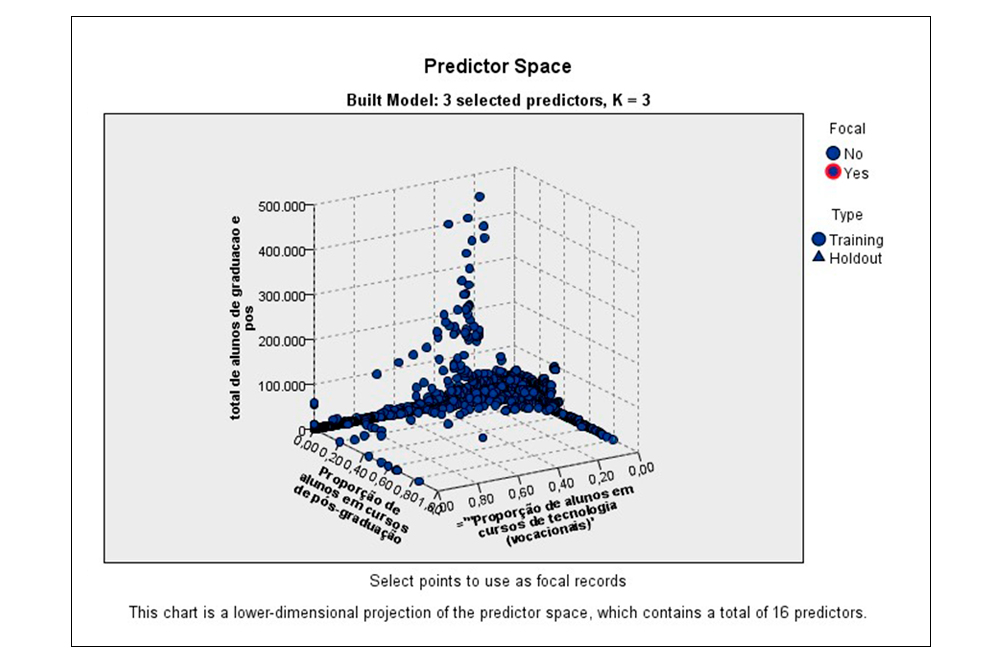

For this project, we also experimented with different clustering techniques, such as the proximity analysis illustrated in Graph 1. It is a three-dimensional graph, whose main vectors are the proportion of students in postgraduate courses, the size of institutions, in number of students, and the proportion of students in vocational courses. Although interesting, in this type of analysis, the result depends on the number of variables considered, not necessarily including the important factors that we know.

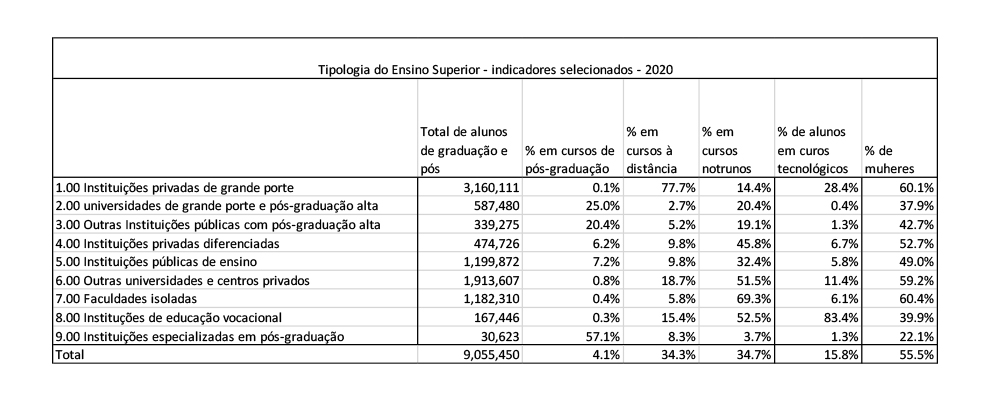

More promising has been the intentional use of some variables that we consider strategic to better understand the differentiation that has been occurring in the system. In this project, we are resuming the classification of nine types of Brazilian higher education institutions, whose main axes are size, legal status (public, private and philanthropic), the proportion of students in postgraduate courses and the proportion of students in short, or vocational courses. Table 2, below, presents the typology used, with some indicators related to the characteristics of enrolled students (2020), which vary significantly between the different types. It makes it possible to clearly distinguish between different types of public institutions and provides additional information about small institutions focused on research and postgraduate studies, that other approaches do not identify.

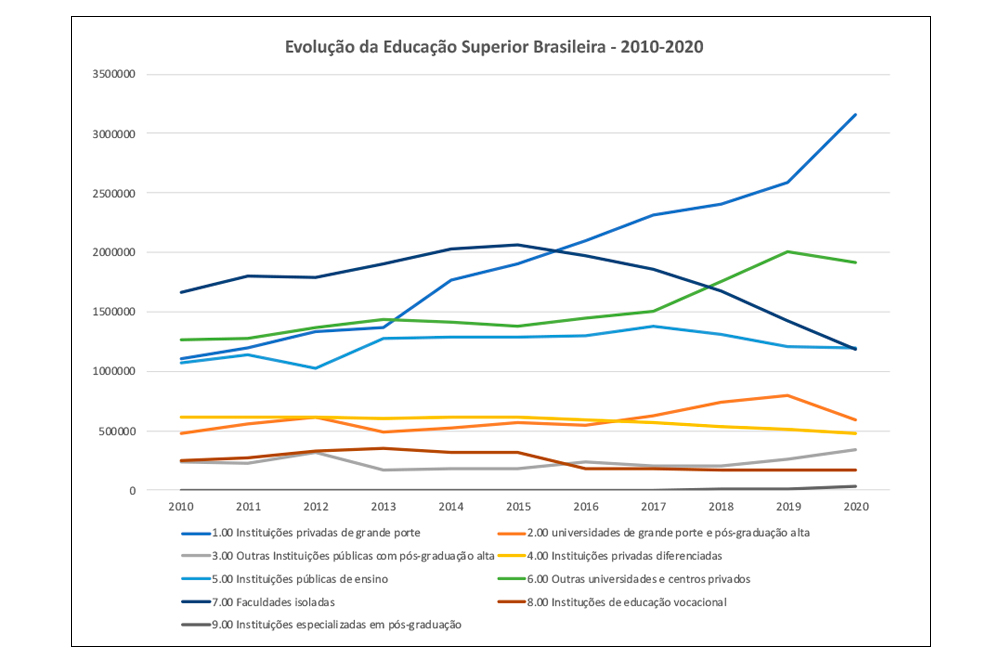

Access to data from different years also allows for an unprecedented view of the evolution of Brazilian higher education, as shown in the graph below, in which we observe that growth was almost exclusively concentrated in the first type of institution, large scale private higher education institutions, aimed mainly at remote learning and evening courses education.

The same type of analysis can be carried out regarding postgraduate studies, showing that 48.5% of doctoral students in 2020 were concentrated in the 13 institutions that are part of group 2; and they still concentrated 35% of the production of articles by Brazilian institutions indexed in the Web of Science (InCites database) in the last ten years.

As it happens in the United States and other countries, [3-4] the existence of an integrated database that is constantly updated and of an appropriate typology, can become a powerful instrument for proper knowledge and continuous improvement of the higher education system in its various dimensions.

Author

Simon Schwartzman is a sociologist, member of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and visiting researcher at the Institute of Geosciences at Unicamp

References

[1] SCHWARTZMAN, S.; SILVA, R. L.; COELHO, R. R. Towards a typology of Brazilian higher education: concept testing. Advanced Studies, v. 35, p. 153-186, 2021. ISSN 0103-4014.

[2] BARBOSA, M.-L. et al. Higher Education in Brazil: Institutional actions for the retention of students in public and private sectors. In: PINHEIRO, R.;BALBACHEVSKY, E., et al (Ed.). The impact of COVID-19 on the institutional fabric of higher education: Accelerating old patterns, imposing new dynamics, and changing rules?: Srpinger, 2023 (forthcoming).

[3] MCCORMICK, A. C. Classifying Higher Education Institutions: Lessons from the Carnegie Classification Clasificación de las instituciones de educación superior: lecciones de la Clasificación Carnegie. Pensamiento Educativo. Revista de Investigación: Educacional Latinoamericana, v. 50, p. 65-75, 2013

[4] VAN VUGHT, F. Mapping the higher education landscape: Towards a European classification of higher education. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. ISBN 904812249X.