Text originally published in Jornal da Unicamp. The original version, in portuguese, can be accessed by clicking here.

The current four-year postgraduate evaluation (2021–2024) will provide information on the social impacts of all programs in the country. This evaluation follows the previous one, which had already begun collecting this information from the programs.

Since it has become a consensus that over 90% of Brazilian scientific production comes from postgraduate programs[1], it is worth examining what lies ahead regarding the impact of Brazilian research.

The 50 evaluation forms—one for each field of knowledge—were created by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes) and the researchers who work in Capes committees. These forms contain three sets of indicators that programs must meet, presenting their data and texts for evaluation by the respective committees.

These three sets of indicators, carrying equal weight in the final scores, are: program, training, and societal impact. The first two are related to indicators directly linked to the functions that Capes has historically assigned to postgraduate education: scientific production, human resource training, and program coherence and consistency.

What interests us here is the third group—the societal impact.

By examining the 50 evaluation forms for the areas of knowledge in this four-year cycle, which will be assessed in 2025, we see that this third group of indicators is divided into three sub-items:

3.1 – Impact and innovative nature of intellectual production based on the program’s nature;

3.2 – Economic, social, and cultural impact of the program;

3.3 – Internationalization, local/regional/national engagement, and program visibility.

Among these three sub-items designed to measure societal impact, only the second one (item 3.2) explicitly requires indicators of social and economic impact. However, it is precisely this item that has the lowest weight in the evaluation forms—on average, slightly below 30% of this group, representing approximately 10% of the total indicators in this four-year evaluation.

Meanwhile, items 3.1 and 3.3 rarely contain indicators of social and economic impact. The first (3.1) is related to the scientific impact of publications, while the third (3.3) focuses on the international, regional, or national reach of research.

Even within item 3.2, some areas list indicators that, according to any standard science, technology, and innovation (ST&I) manual or methodological guide, could not be considered economic and social impact indicators—such as the “organization of conferences, advanced schools, and national and regional workshops.” That’s fine. I also consider this an important indicator, but it already has a designated place in other sections of the evaluation forms.

It is interesting to note that different fields interpret socioeconomic impact in very particular ways and also allocate the weight of these indicators differently. Fields like philosophy, history, and religious studies assign greater weight to item 3.2 compared to astronomy, physics, and mathematics.

All areas of knowledge, without exception, could develop better and more robust indicators of socioeconomic impact. There are examples worldwide. This has been happening in several countries for some years now.

A 2025 article published in the journal Research Evaluation analyzes how three countries are systematically assessing their research using social and economic impact indicators—sometimes also including environmental, cultural, and other dimensions. These countries are: the United Kingdom, with the Research Excellence Framework (REF 2014 and 2021); Australia, with the Engagement and Impact Assessment (EI 2018); and Hong Kong, with the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE 2020). These indicators are analyzed to understand what is being identified as the impact of scientific and technological research in these countries.

It is quite interesting. Let’s take a closer look.

All three countries have similar evaluation models, sometimes linking performance to funding. The study conducted by the authors of the aforementioned article analyzed 7,275 impact studies from the three evaluation systems in these countries.

Their research question was: “How is the value of research expressed in the three countries that have similar impact evaluation models?”

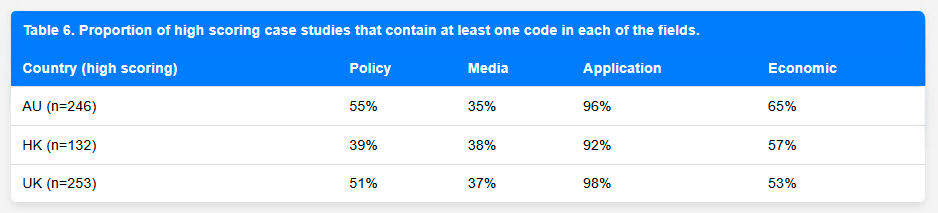

Using an artificial intelligence (AI) tool, the authors categorized four themes of socioeconomic impact:

a) Policy impact

b) Media impact

c) Applications

d) Economic impacts

Table 1 below presents the frequency with which these themes appear in evaluations.

Table 1 – Frequency of impact themes in the studied countries

As can be seen, the spectrum is broad and reveals how research in these countries has been addressing impacts beyond the academic realm.

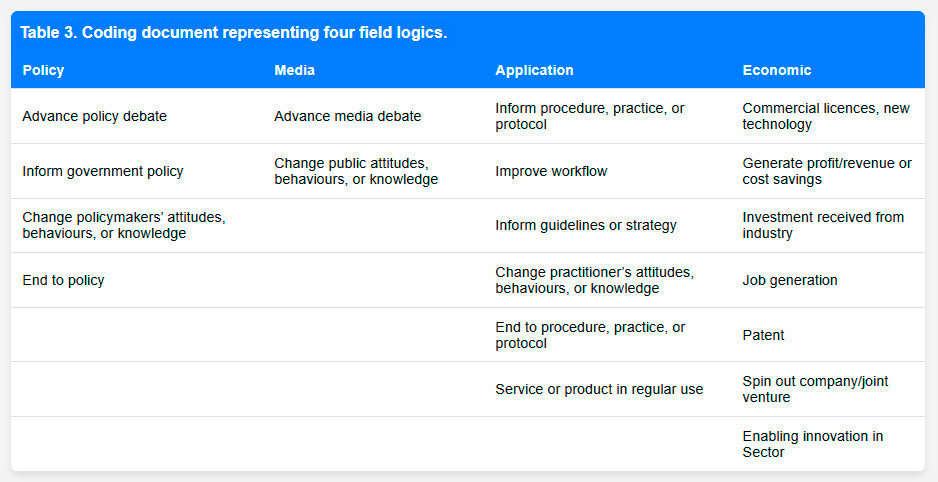

When analyzing the relative frequency of these impact indicators (or topics), the results show a prevalence of the Application theme. Table 2 details the indicators for each evaluation theme.

Table 2 – Impact indicators across the four impact themes

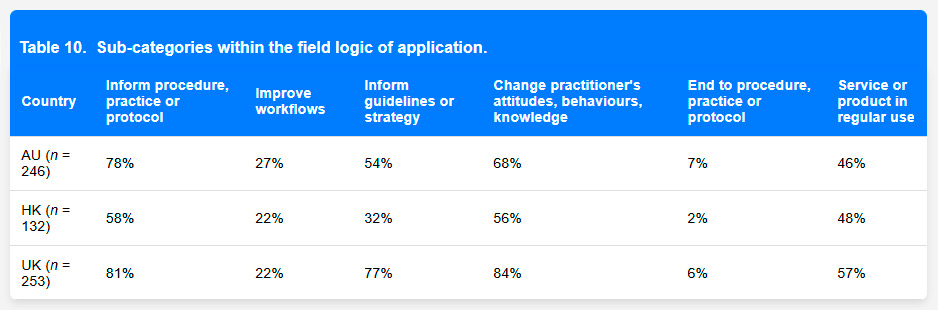

As shown in Table 2, Application is by far the theme through which researchers and institutions most address the impacts of their research. Perhaps because it is a broad category encompassing a wide variety of outcomes. As Table 3 shows, Application remains the primary theme through which researchers and institutions address the impacts of their research.

Table 3 – Distribution of impacts by sub-themes within the “Application” theme

Providing procedures, practices, and protocols, informing guidelines and strategies, and changing attitudes and behaviors are the most frequently addressed indicators. Next comes having services or products in use by society. The least frequent item is using research results to discontinue or finalize procedures, practices, or protocols.

If we group overlapping indicators, we can conclude that the most frequent effects of research results reported in the three cases have been “creating evidence and information that enters societal use.”

Although detected less frequently in the study, the other impact themes—policy, economic, and media impacts, as seen in Table 2—also stand out and are used with varying intensity in different countries. According to the study, this variation reflects national cultural characteristics and preferences.

What the practices show is that it is entirely possible to measure impacts beyond the academic sphere with relatively convincing indicators, scientifically validated within their respective contexts.

Changing the course of an evaluation as structured, rigorous, and consolidated as that of Capes takes time. For obvious reasons, but mainly because it involves learning and accepting new things and letting go of entrenched ideas, especially those that have created hierarchies in the scientific world.

Almost everyone agrees that understanding the societal impact of research is valuable—after all, impacts are everywhere. But when it comes to implementation, few follow through. There is a power dynamic at play here, acting as a brake on change.

The last two four-year evaluations, especially the current one (2021-2024), will allow us to understand if and what is changing in Capes’ evaluation model. To do so, we will need an evaluation of the evaluation itself.

I am certain it is not the intention, but we must be cautious so that some indicators in the evaluation forms are not interpreted as mere “impactwashing.”

[1] This figure, mentioned in the article by McManus et al. (2021), needs to be revisited. It is well known that postgraduate programs report as their own any possible publication involving faculty members, researchers, and even students. Hypothetically, and subject to verification, these numbers may be inflated.