Document points to the importance of advancing technology parks in the country…as long as it also encompasses its entire ecosystems

Author: Guilherme Cavalcante Silva

It is universally recognized that one of the main factors in socioeconomic growth and its dynamization is investment in innovation processes. This is especially true for “emerging” countries such as Brazil. In this sense, in the midst of the many bad news, Brazil can be proud of having improved its position in the latest Global Innovation Index, published in the second half of 2020, jumping four positions (it is currently in 62nd place among 131 countries evaluated), occupying the fourth place in Latin America – even though the scenario of technological capability development is still far from ideal, as this study points out. In this context, technology parks are reacher higher grounds in the country.

Altogether, according to data from the National Association of Entities Promoting Innovative Enterprises (Anprotec) Brazil has 43 technology parks in operation and 60 in implementation; of these, 36 have as its main cluster the area of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), 25 biotechnology, and 22 the energy area. But, after all, what are technology parks? Forget the scenario of Silicon Valley and its huge technology companies. Technology parks are much more than a conglomerate of ICT companies. They play a vital role in nurturing local innovation ecosystems and promoting production, research, and innovative entrepreneurship.

The Cabinet of Entrepreneurship and Innovation of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications (MCTI) has recently commissioned the creation of a methodology for the classification and evaluation of technology parks in Brazil, aiming not only the development of strategies, but also an optimal allocation of public resources for their creation and maintenance. The project headed by the Laboratory for Studies on the Organization of Research & Innovation (Geopi/Unicamp), was coordinated by three InSySPo members: Bruno Fischer, Paola Schaeffer, and Camila Zeitoum. The report was sent to the ministry in December 2020.

What are technology parks?

The definition of a technology park is not straightforward. Some definitions are stricter, while others appear more broadly. In general, according to Protec’s definition, a technology park is a planned industrial production complex of scientific-technological based services, with a formal, concentrated, and cooperative character, bringing together companies whose production is based on research and development, promoting a culture of innovation, competitiveness, and business training with the aim of increasing the wealth of a region. In short, it is based on the geographical and planned concentration of companies oriented towards research, development, and innovation. Therefore, not every industrial zone is a technology park.

With the purpose of providing a methodology to help the government’s promotion of technological parks, the report breaks some common notions associated with them, such as the idea that their massive implementation, by itself, can generate a socioeconomic boom in the area where they are located. The report shows the importance of the ecosystem where the park is located and the productive alignment between the park and local policies. “The park is not the main element for promoting regional development. It appears as an important stimulator for something that is already established,” warns Zeitoum. Investment in parks without proper planning or considering for the local ecosystem and the region’s development stage as well as the availability of qualified human resources are the perfect recipe to produce “white elephants”, bringing large deficits to public funds.

“If we could create a technology park in an economically peripheral region and expect this to generate development in that area, it would be fantastic. But this is not what happens in real life. What we realize, based on evidence is that you can come up with a technology park and it becomes a drain. The more public money you put in, in the absence of certain conditions, the more it sucks without giving results that justify its existence. Why? There are things to be done before making that step. First, you need to understand the reasons behind the lack of socioeconomic development there. These are complex issues, and the park will not supply everything needed for regional development,” explains Fischer. It is worth remembering that in 2020 alone, the portfolio’s budget reached BRL 15 billion [around USD 2.65 billion].

Socioeconomic development demands more than focusing on isolated initiatives, such as building technology parks. This fact points to the difficulties involved in reducing economic and technological asymmetries between regions in a country, such as the one found between the North/Northeast and the South/Southeast of Brazil, and between blocks of countries, such as the one between Latin America and Europe/North America. “There is no point in creating something because it is an international trend. There must be complementary assets for every single project in the region. Otherwise, the results will fall short of the expected. The big issue is that these changes in orientation and development are not quick or easy,” concludes Fischer. One of the strengths of the methodology is precisely to highlight the role of the park within the ecosystem in question and its potential in terms of internal and external interactions, pointing out aspects where alignments and specific investments are necessary.

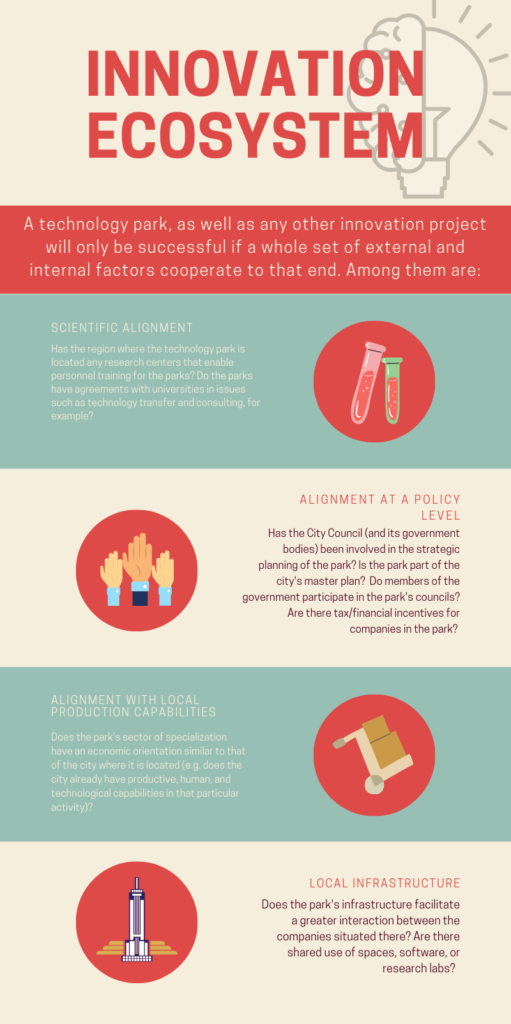

The methodology highlighted the importance of the so-called “innovation ecosystem” [see infographic below] in the creation of innovation projects. This expression, common among innovation researchers, accounts for the interplay between multiple factors for the success of innovation projects. These factors go beyond the “four” walls of the companies and their financial and material resources, reaching less “tangible” aspects such as: public policies at the local level; pre-existing industrial, technological, and economic orientation in the area; scientific and human resources capabilities linked to the region (e.g., universities or research centers), among others. “The parks are not detached from their context. They depend on university training people for their staff, as well as the engagement from the local government. Other companies will demand or supply products to the companies from the park. These relations are vital, otherwise the park becomes a disconnected complex of unproductive and financially troubled companies”, Schaeffer points out.

The Methodology of Evaluation of Technology Parks in Brazil (MAPTec) built several indicators to evaluate (from 0 to 1) each dimension of a technology park – namely: external and internal ecosystem/interactions, governance, and results/impacts, finishing with the display of three characteristic profiles of Brazilian technology parks: the leader park (with the highest score, <0.85), the follower park (median scores, 0.60-0.85) and the embryonic park (low scores, >0.60). Although not conducting an exhaustive survey on the number of parks located in each of these profiles, the team responsible for the methodology proposed a series of initiatives to optimize the evaluation and stimulate the transition of parks to more consolidated stages of organization. “We developed the methodology with the intent of showing the public manager what are the strengths and weaknesses of each park, considering their different maturity stages. This way, s/he can define priorities in her/his planning and spending,” adds Zeitoum.

In addition to demonstrating the importance of calming the spirits when it comes to fostering innovation at all costs, the methodology brings to light the challenge of systematizing and evaluating the impact of public and private initiatives in Brazil. This was the main suggestion made by the researchers, which involved the following recommendations: 1) compulsory submission of information from companies and technology parks in case they want to compete for financial incentives from the federal government; 2) systematization of the data collection process in technology parks; 3) continuous use of tools for classification, monitoring, and impact assessment of parks before, during, and after the decision-making process on funding; and 4) engagement of the academic community in the evaluation and classification of technology parks. The request for the creation of an evaluation methodology for technology parks by the MCTI is an important step in this direction. “Our intention is to support the establishment of a culture of evaluation of investments made, especially in the public sphere. Evaluation analysis here in Brazil is still far behind from what is done in Europe. We need to get used to, and I am not just talking about the parks, monitoring the results and impacts of public programs,” expresses Fischer.

Meanwhile, Brazil is witnessing a growth in the number of technology parks and has several good examples of parks that became important hubs for regional development, as shown below. “The moment has been one of growth in the number of parks in the country. With the development of a healthy innovation ecosystem, associated with better infrastructure, partnerships with universities, interaction between local government and technology parks, fostering the creation of scientific, productive, and technological competencies, and a more consistent impact evaluation, the parks have everything to generate significant socioeconomic gains in Brazil,” concludes.