Estudo avalia impacto do ecossistema universitário na intenção empreendedora dos alunos

Autor: Guilherme Cavalcante Silva (InSySPo) / Para a versão em inglês, clique aqui

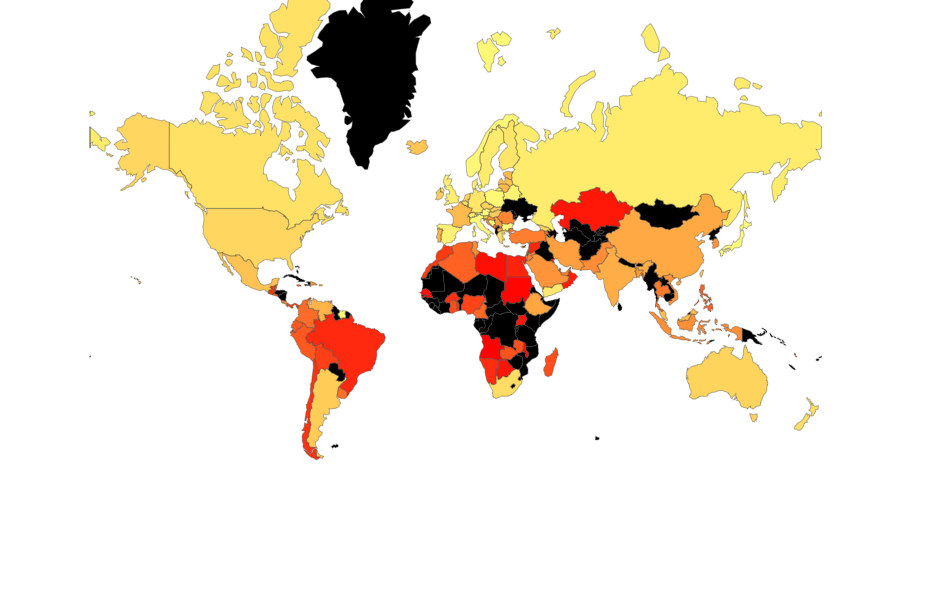

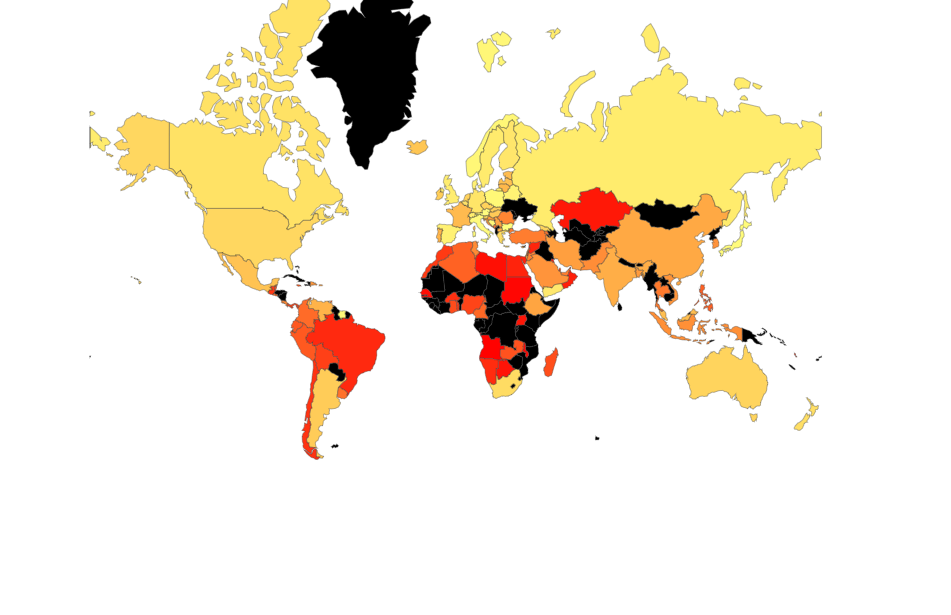

Passaram-se anos, veio uma pandemia, mas uma coisa não mudou no Brasil: o anseio por empreender. Embora o número de empreendedores estabelecidos no país tenha caído pela metade no país em 2020 (de 16,1%, em 2019, para 8,7% em 2020), o índice de atividades empreendedoras em fase inicial até mesmo aumentou (ligeiramente), subindo de 23,3% para 23,4%, segundo dados do Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). As porcentagens se referem à quantidade da população nacional registrada como empreendedores em fase inicial ou estabelecida.

Quando a intenção de empreender entra em questão, os dados são ainda mais enfáticos. Mais da metade da população brasileira (52,7%) tem intenção de começar um negócio próprio em até três anos, índice que estava em 30% em 2019 – Brasil é um dos líderes globais neste ranking. A pergunta que paira no ar ante esse cenário é: como aproveitar esses números e favorecer ainda mais o empreendedorismo no país? A resposta não é fácil e envolve não apenas ações das esferas governamentais, como também de outras áreas. Uma delas é a universidade, um dos principais elementos do ecossistema de empreendedorismo.

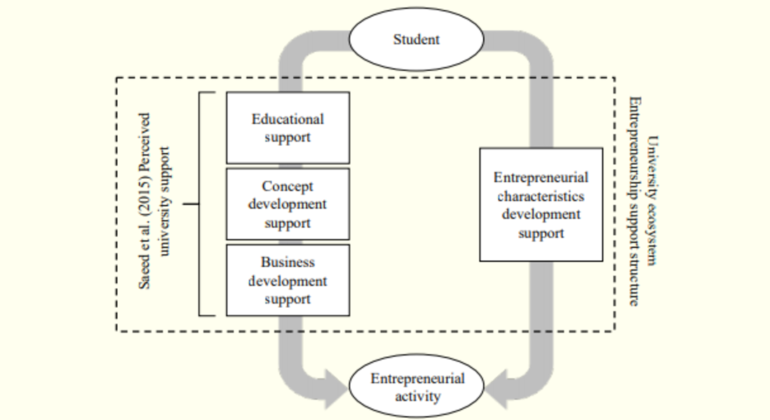

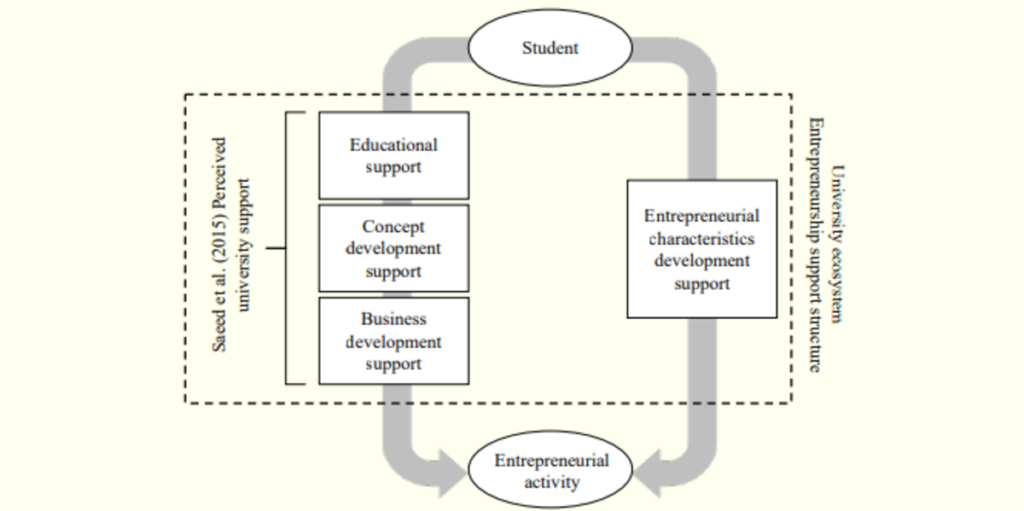

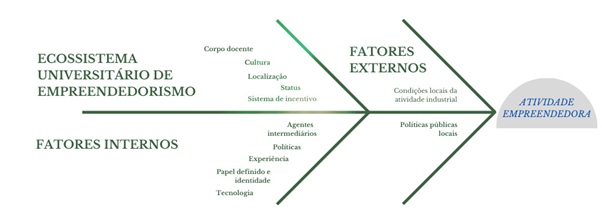

Motivado por esse tema, Matheus Campos, pesquisador de pós-doutorado no programa Innovation Systems, Strategies and Policy (InSySPo), da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), fez da relação entre o ambiente da universidade e o desenvolvimento de características empreendedoras o assunto de sua pesquisa doutoral. Recentemente, ele publicou um artigo, em co-autoria com os pesquisadores Gustavo Salati e Ana Carolina Spatti, ambos também da Unicamp, na Brazilian Administration Review, apresentando os resultados de um modelo avaliativo que utilizou para compreender os diferentes modos em que o ambiente universitário no Brasil impacta o desenvolvimento de características empresariais nos alunos, e, consequentemente, o próprio modo em que universidade e empreendedorismo interagem. O artigo é intitulado “Do University Ecosystems Impact Student’s Entrepreneurial Behavior?“.

No artigo, os autores criaram um modelo conceitual de análise e extraíram dados de sete universidades públicas brasileiras (UEA, UFCG, UnB, Unicamp, USP, UTFPR, UFRGS), localizadas nas cinco regiões do país. Os resultados demonstraram o que, de modo geral, os estudos na área já sabiam: as universidades possuem uma influência no desenvolvimento de intenção empreendedora (intenção de abrir um negócio) por parte dos alunos. Porém, o escopo de tal influência é bem menor do que se pensava. “O que nosso estudo demonstrou é que o papel mais importante da universidade, em relação ao empreendedorismo, não é o incentivo para que o aluno abra uma empresa, mas a sua atuação no desenvolvimento de características voltadas ao empreendedorismo”, sublinha Campos. Em outros termos, treinamentos motivacionais, cursos e uma atuação voltada para que o estudante abra empresas no futuro, embora importantes, são menos eficazes do que o preparo voltado para características empreendedoras, como reconhecimento de oportunidades, perseverança e habilidade de pensar em soluções inovadoras. Afinal, um dos achados do estudo foi de que, nas universidades pesquisadas, a intenção empreendedora está muito mais relacionada com as características pessoais dos próprios estudantes do que com ações da universidade nesse sentido.

O estudo se soma a outras pesquisas da área conhecida como “ecossistema do empreendedorismo”, que avalia a atividade empreendedora em sua conexão com diferentes fatores sociais, políticos, econômicos e educacionais, fatores estes que ultrapassam as “quatro” paredes das empresas e seus recursos financeiros e materiais. “Mesmo algo como a intenção de empreender, por parte dos alunos, está direcionada a fatores tão distintos quanto a sua localização geográfica, isto é, se este aluno está na região Norte/Nordeste ou Sul/Sudeste do país, como nosso estudo demonstrou”, aponta Spatti. “Em um o maior nível de capacitação vai estar consequentemente ligado a um maior estímulo para empreender, em outro, com o mesmo nível de capacitação, o estímulo pode não vir por diversos fatores, como maior competitividade, por exemplo”, acrescenta Salati. Além do aspecto geográfico, a disponibilidade de capital humano, financiamento, políticas públicas, acessibilidade de mercado, cultural local e presença das universidades são alguns dos outros pilares do ecossistema de empreendedorismo.

Em relação ao contexto mais específico das universidades, diversos fatores influenciam na decisão dos alunos de empreender. Os resultados do artigo, relacionados às universidades brasileiras, demonstraram que um dos principais é o desenvolvimento de características empreendedoras, que impactam diretamente a mentalidade empreendedora dos estudantes. Por outro lado, fatores como suporte à abertura de negócios constituíram pesos negativos na amostra. “Em rankings globais de intenção empreendedora, estamos [Brasil] sempre no topo. Mas, ao mesmo tempo, paradoxalmente, ainda há uma certa dificuldade cultural no país em relação a empreender e a ter uma relação mais próxima entre empresas e universidades”, reflete Salati. “O que as pesquisas têm mostrado é que se a orientação da universidade for para o preparo para o mercado de trabalho, o estudante seguirá esse rumo. Por outro lado, se lá ele tiver contato com abertura de empresas, patenteamento, a tendência é que siga esse caminho”, conclui Campos. Embora universidades como USP e Unicamp se destaquem na relação universidade-indústria em termos de investimento e patenteamento, o cenário brasileiro, no geral, ainda é de pouco investimento em P&D (cerca de 1% do PIB, porcentagem bastante superior em países desenvolvidos) e pouca participação da iniciativa privada.

A pesquisa é um indicativo de que uma atividade empreendedora mais intensa no contexto das universidades brasileiras pode não vir de um frenesi sobre empreendedorismo no contexto da sala de aula ou da mera reprodução de modelos “certificados” por instituições norte-americanas ou europeias. “Os nossos achados apontam que as universidades brasileiras são muito boas na questão do ensino e oferecimento de aulas, palestras, cursos e workshops sobre empreendedorismo, mas faltam mecanismos de suporte para auxiliar o estudante a efetivamente abrir uma firma. Tudo isso está relacionado a uma cultura mais ampla, tanto dentro como fora da universidade, em relação ao empreendedorismo que amplia um gap entre ensino e empresas”, reflete Campos.

O artigo completo se encontra disponível aqui.